May 2022.

How would you know if a female colleague was struggling with mental health?

And what would you do about it?

How can you create a working environment that supports maternal mental health?

This article aims to help you consider these questions by providing reflections on my own lived experience of postnatal depression.

Trigger warning: This post contains content that may be triggering for some people. Sources of help and advice are listed at the bottom of the page.

Maternal Mental Health Matters

Around 10–20% of women experience mental health problems in the perinatal period (during pregnancy and the first year after having a baby).

This figure is likely to be much higher since covid hit in 2020.

If this isn’t shocking enough, we know that maternal suicide is the leading cause of direct deaths amongst women in the first year after giving birth.

When the pandemic reached the UK, maternity services were thrown into chaos in a matter of days. Expectant mothers attended ultrasound scans alone, many (like myself) gave birth alone, and some, devastatingly, received the most dreaded news that any mother can receive, alone.

Baby clinics were cancelled. Health visitor appointments moved online. Concerns about newborn health were discussed over the telephone. Assessments of physical development were based on photographs. Masked mothers weren’t allowed to kiss their screaming babies during routine vaccinations. Mental health screening took place via video call to shared offices where strangers rummaged through cabinets in the background.

Those of us who had babies during the early days of covid now find ourselves juggling work with childcare and motherhood. As our babies grow into toddlers, we try not to worry about media reports of the developmental delays caused by covid. We are rebuilding our professional selves after maternity leave, while also trying to establish new connections with other mothers, who we missed so sorely in those early days.

Covid has increased and intensified the factors that contribute to maternal mental health issues in the perinatal period and beyond. Sadly, services to support mothers still have not returned to their pre-covid state, despite our lives returning to a semblance of normality in almost every other sphere.

Why does this matter to you?

Because maternal mental health matters to us all. This is particularly true in sectors — such as the tech sector, in which I work — that are actively trying to recruit more women. It is not enough to have strategies for attracting and recruiting more women into the workforce; we have a responsibility to ensure that we create inclusive working environments to support all our staff.

From a business perspective, greater diversity and inclusion in the workplace have been proven to increase innovation and productivity. Further, the cost of recruitment is so great that we need to focus on retaining diverse talent.

Employers have a duty of care for their staff, and we all have a moral responsibility to support our colleagues where we can.

The first step towards supporting maternal mental health in the workplace is to understand the challenges that women face. This article focuses on a small sub-section of women — expectant mothers and those who have young children — but this is a good illustration of the point.

The first step towards supporting maternal mental health in the workplace is to understand the challenges that women face.

When I returned from maternity leave after giving birth to my second child during the first lockdown, lots of people asked how my maternity leave went. I would explain briefly that it was unusual, and challenging, and isolation with a baby is really difficult, but I love my baby, and I’m grateful for my family’s health.

This response seemed to surprise some people. Perhaps they hadn’t thought about how the pandemic looks and feels to expectant mothers and women with newborns. That’s understandable. There’s been so much upheaval over the past couple of years that we’re just starting to come to terms with how the pandemic has affected people in different ways.

And yet, my brutally honest answer to the question would have been quite different. I would have mentioned the sleepless nights anxiously trawling the internet to discover whether the virus would harm my unborn baby; the terror of anticipating going through labour on my own; revulsion when strangers touched my newborn baby; the exhaustion of raising a second child without any help from extended family and whilst home-schooling my eldest; the guilt of being too tired to spend quality time with either of my children or my husband; the grief of losing precious time alone to bond with my baby.

Of course, it wouldn’t have been appropriate for me to go into detail about these things. But this is the reality of my experience. It is my honest answer to the question. And it differs greatly from how I talk about it at work.

The things that most greatly affect our mental health tend to be the things that we would rather not talk about. With anyone. Especially people we work with.

I’m not proposing that colleagues should become counsellors, or that we should wear our hearts on our sleeves. But we need to remember that we only ever see the tip of the iceberg when we connect with other people.

My experience has taught me that we need to find ways of supporting our colleagues proactively, rather than waiting for them to tell us about the challenges they face, or trying to spot tell-tale signs of distress.

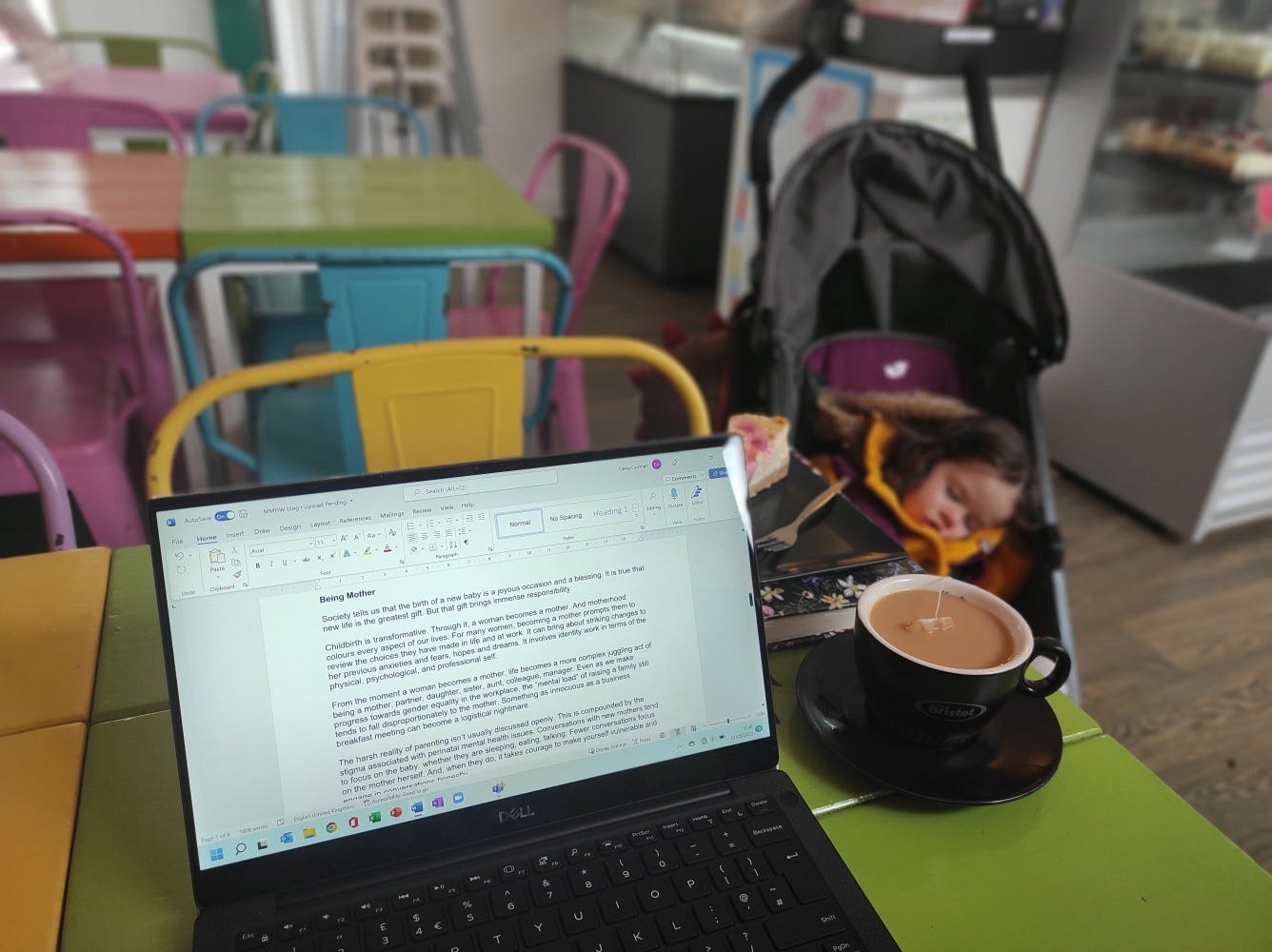

Being Mother

Society tells us that the birth of a new baby is a joyous occasion and a blessing. For me, this is absolutely true. My children are my life. I became me when I became a mother. New life is the greatest gift, but that gift brings immense responsibility.

Childbirth is transformative. Through it, a woman becomes a mother. And motherhood colours every aspect of our lives. For many women, becoming a mother prompts her to review the choices she has made in life and at work. It can bring about striking changes to her previous anxieties and fears, hopes and dreams. It involves identity work in terms of her physical, psychological, and professional self.

From the moment a woman becomes a mother, life becomes a more complex juggling act of being a mother, partner, daughter, sister, aunt, colleague, manager. Even as we make progress towards gender equality in the workplace, the “mental load” of raising a family still tends to fall disproportionately to the mother. Something as innocuous as a business breakfast meeting can become a logistical nightmare.

They say that “it takes a village to raise a child”. Covid took that away from us. We raised our babies alone behind closed doors. We soothed our c-section scars while breastfeeding our babies, while home-schooling our older children, while doing our online shopping, while preparing ourselves for our return to work.

The harsh reality of parenting doesn’t tend to be discussed openly. A mother who is struggling can feel that she is the only one who is finding it hard to balance the competing demands of life. In reality, the juggle is real; the struggle is real.

This is compounded by the stigma associated with perinatal mental health issues. Conversations with new mothers tend to focus on the baby: whether they are sleeping, eating, talking. Fewer conversations focus on the mother herself. And, when they do, it takes courage for a woman to make herself vulnerable and feel safe enough to speak openly.

Being a mother does not mean being a martyr. We don’t have to suffer. We shouldn’t have to endure our struggles privately. We should feel comfortable talking about our experiences without fear of being judged. We need to be supported to access help when needed, whether from a friend, a medical professional, a colleague, or an employer.

But what can you do as an employer or a colleague?

Hidden Suffering

There is a good chance that you have worked with someone who has been affected by perinatal mental health issues: a mother, her partner, or a member of her family.

Have you?

How do you know?

Seven years ago, after the birth of my first child, I had severe post-natal depression. At work, my colleagues weren’t aware of this, at least not until much later. I continued to excel in managing a team and leading a high-profile national educational partnership. I looked presentable, I spoke confidently in meetings, and I worked effectively with colleagues and external partners to manage a complex workload.

While I continued to succeed at work, my life at home was crumbling. The effort at work used up all my resources, and I had nothing left for my family. After work, I would collapse on the sofa with a paralysing numbness that prevented me from smiling or playing with my toddler. I had no energy to cook or clean or even talk. I lay in a dark fog, wondering whether I even existed.

Looking back, as if on another person’s life, I’m confused at how happy I look in photographs from that time. It reminds me that appearances can be deceiving. A person might look like they are thriving, when they are only surviving.

The impact of postnatal depression was very visible behind the closed doors of my house. It shocked my husband and my close family. My mind wandered into dark places. I tried so hard to maintain high standards at work that eventually it became too much and I had to take time off to recover.

Even now while I write this — some 7 years afterwards — I feel slightly uncomfortable sharing this experience. I wonder what my colleagues might think if they read it. I worry that future employers might read these words and interpret them as weakness.

But this is precisely why I want to share my experience. We need to break the stigma. We need to let others know that they are not alone. We need to encourage each other to reach out for help. We need to know that we can get through dark days and come back ten times stronger.

Supporting Others

We can’t always tell whether a person is experiencing mental health issues just by looking at them. Their performance might not waver. Their commitment and drive might seem greater than ever. But they might be suffering privately.

What can we do to support people in this situation?

In this situation, I’m reminded of the phrase “prevention is better than cure”. It is true that many people display visible signs of depression. But not all people do, at least not in public. We shouldn’t continue with business as usual, providing support only when we see signs of mental distress, potentially after months (or years) of an individual’s suffering.

After experiencing severe postnatal depression after the birth of my first child, I came to realise the things had helped me recover and come back stronger. This meant that, when I experienced postnatal depression after the birth of my second child, I was able to recover much quicker.

Below is a list of some of the things that helped me recover from two bouts of postnatal depression. These are not “tips” or “advice”, but rather they are snippets of learning about myself.

Everybody’s experience of postnatal depression is different. While I’m a Mental Health First Aider, I’m not a medical professional, and I’m not qualified to give advice. But I do have lived experience of working through postnatal depression.

I hope this list will spark reflection and discussion of how we can develop working environments that support maternal mental health.

Most advice that exists online and in books tends to focus on people who are experiencing perinatal mental illness, on their families and friends, and on healthcare providers. I hope this article might encourage us to bring the conversation into the workplace.

I also hope it might help people who are experiencing mental health issues; I’ve included links to sources of information and support at the end of this article.

5 things that helped me in the workplace…

1. Working from home

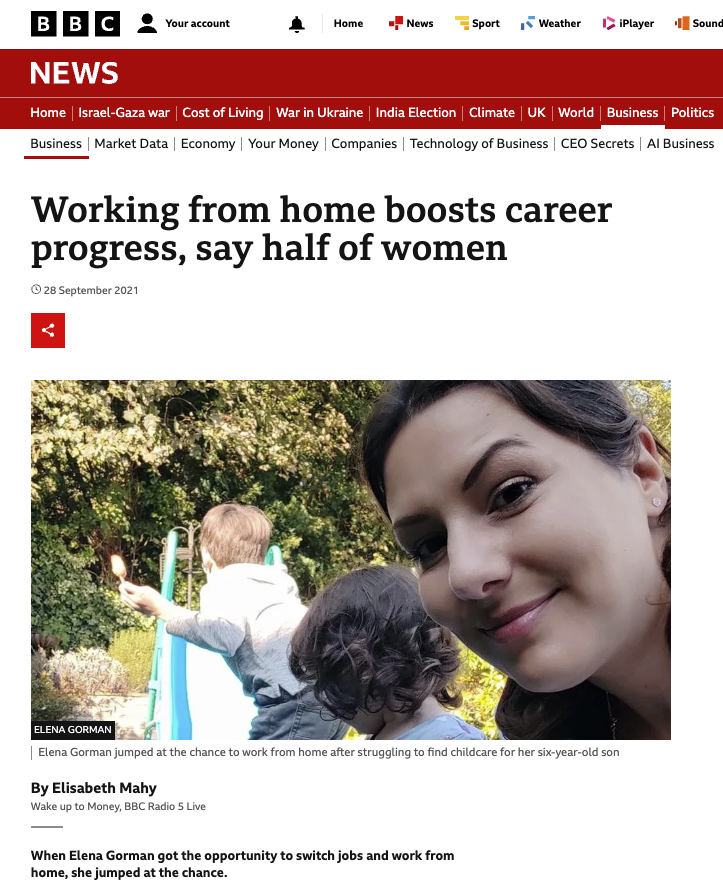

After the birth of my first baby, I requested to work from home for one day per week to give me headspace. My proposal wasn’t agreed, as it was felt that managers couldn’t work effectively from home, and that it would set a precedent for others. This decision was a major contributing factor to the decline in my mental health.

After the birth of my second baby during the pandemic, the world of work looked entirely different, and working from home was the norm. I returned from maternity leave to a new role that was 100% remote. I had the headspace that I needed, and I had the benefits of a world accustomed to remote working. I was comfortable, my confidence grew, and I achieved great things with my team.

Now in another new role (still recovering from postnatal depression, but doing extremely well), I work from home, but I travel to meetings approximately every other day. This arrangement suits me perfectly. Knowing that I have flexibility to set my own calendar makes all the difference to me.

2. Part-time / Full-time

The option to work part-time is extremely important but it’s not a panacea.

After the birth of my first baby, I wanted to work full-time, but I was encouraged to consider working part-time (4 days per week) to achieve work-life balance. But my workload wasn’t reduced, and my work accumulated. My “day off” with my baby was on a Wednesday, which meant that every working day felt like I was either starting my working week or ending my working week. All of this had a direct impact on my mental health.

After the birth of my second baby, I started a new job that was the equivalent of 4.5 days per week. I joined an incredibly supportive team of women (all of whom were mothers) and I was trusted to work flexibly. My week was condensed into 4 slightly longer days, so that I could take a Friday off work with my child. This worked beautifully! For the first time in my life, I had work-life balance.

Now, I work 4 days per week, alongside two extremely supportive women (who are also mothers). We openly discuss how our families are our top priority, and we are given flexibility to schedule our work around our family commitments when needed. My workload is heavy but manageable. I have never felt so trusted and empowered. This has been incredible for building my confidence and making me fully committed to my role.

The ideal working arrangement varies for each woman depending on her job and unique circumstances. Employers should initiate open and supportive conversations in which all options are explored together, including part-time, full-time, flexible hours, condensed hours, and non-working days.

3. Realistic expectations

Becoming a mother means that you are needed by your child at all hours of the day and night. This is difficult to manage when you are used to working 60–70 hour weeks. I had to lower my expectations greatly: of how long I could work each week, what time I had to leave the office, and what I could achieve in the time available to me.

Employers can help by creating a positive culture that isn’t based on rewarding (explicitly or implicitly) around-the-clock working. They can help by articulating that employees are expected not to work during weekends or holidays. They can make sure that targets in professional development plans and annual appraisals are realistic and reflect the number of hours in an employee’s contract. They can provide positive feedback to reassure women that their efforts and achievements are noticed, and that their contribution is valuable and valued.

4. Mindful being

It sounds trivial, but I started a new hobby of making fabric flowers after having my first child. This kept my hands busy, occupied my mind, and gave me a sense of achievement. Studies have shown a link between creative crafts and improved mental health. Likewise, working on small creative projects with a clear outcome or impact have a similar effect for me at work.

I also try to practice mindfulness with my children, making time “just to play”, and giving them my undivided attention. Recently my colleague, the fantastic Helen Tong, has spoken about this as “being in the room”; a phrase that captures the mindset perfectly. Family time must be protected and respected. Wherever possible, out-of-hours messages should be limited to email (with a clear expectation that an immediate response is not required), and not through social media channels.

5. Extended maternity leave

It might not be possible in all organisations, but the option for extended (unpaid) maternity leave was absolutely central to supporting my speedy recovery from postnatal depression following the birth of my second child during the pandemic. I needed an extra few months of maternity leave to spend time with my daughter and to prepare myself for my return to work. My employers at the time kindly gave me this opportunity. Returning to work before I was ready would have had a significant impact on my recovery from postnatal depression.

How about you?

Do you have experience of maternal mental health issues: either personally, or through supporting women and other people who have been affected directly or indirectly?

What helped?

Do you have any experiences that you’d like to share?

If you do, please leave your thoughts in the comments!

Sources of information and support

There are lots of sources of information and support available. I strongly urge you to find out more about perinatal mental illness.

It can be difficult to reach out when you are struggling, but I have learnt that accessing support as early as possible is incredibly important. Your GP is a good first point of call, and they can help you find the right support for you, whether that’s talking therapies, medication, or support groups. (All three of these were life-changing for me.)

You can also find lots of information online, including through the following links:

- PANDAS Foundation: A free helpline and support for people suffering from, or affected by, perinatal mental health problems

- Mind: Information about depression and other issues relating to mental health

- The most fantastic article by Eve Canavan (Founder of the Perinatal Mental Health Partnership), listing sources of information and support relating to perinatal mental health: “Support When Mums Need it Most — Perinatal Mental Health Support During Covid-19 and Beyond”.

- Another incredible set of resources produced by Eve Canavan, and the Perinatal Mental Health Partnership, for UK Maternal Mental Health Awareness Week 2022: resources freely available here.

- For those living in the North East of England, I found this Facebook group to be a lifesaver during the pandemic: Antenatal and Postnatal Education and Support North East

- The Postpartum Stress Centre has some useful resources, and I’ve learnt A LOT from books by Karen Kleiman, especially Good Mums Have Scary Thoughts (which I keep by my bed!) and What Am I Thinking? Having a Baby After Postpartum Depression.

- Dads: The Maternal Mental Health Alliance has published a report into the mental health of dads in the perinatal period

- Dads: For dads’ mental health, see the fantastic work of Elliott Rae through MusicFootballFatherhood (MFF). Watch Elliott’s BBC film on mental health support for dads.

References

- Public Health England: Mental Health and Wellbeing: JSNA Toolkit (4: Perinatal Mental Health)

- Royal College of Nursing: Perinatal Mental Health

- MBRRACE-UK: Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care (Lay Summary 2021)

- Forbes Insights: Fostering Innovation Through a Diverse Workforce

About the author

Elena Gorman is wife to a very patient husband, and mum to two cheeky monkeys. She is the Digital Talent Engine Manager for Dynamo North East. She has worked in a number of tech-related roles, including for TechUPWomen at Durham University, The Alan Turing Institute through Newcastle University, and the Creative Fuse North East project at Northumbria University. Elena has a PhD in Theology from Durham University and has published research on female martyrdom in early Christianity.

Leave a comment